| Architecture For Islamic Societies Today |

| |

| 154 |

| |

| PDF Direct Download Link |

| Click for Hard Copy from Amazon |

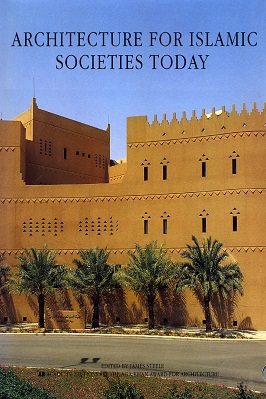

Architecture for Islamic Societies Today

ARCHITECTURE FOR ISLAMIC SOCIETIES TODAY

From th book:

……The new arrivals were met there by a similarly varied array of Egyptian architects, professors, critics and helpers of all sorts.

There followed a series of learned and social events, whose high point was the presentation of the fourth Aga Khan Awards for Architecture in the spectacular setting of Cairo’s Citadel, suitably smartened up for the occasion.

Most of these people knew each other before meeting in Cairo, or, at the very least, they had heard of each other. Many had met before and most will, God willing, meet again.

But few of them had imagined, when they embarked on individual professional careers in so many different lands, that they would eventually belong to a totally unique group, a sort of club without uniforms but with a logo, without rules of membership, practice, or behavior but with a mission and a commitment.

If it had to have a name, the club would probably be called, quite awkwardly, the Network concerned with the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in the lands where Muslims live and work’. But it should not have a name, just as it can never have membership cards

For, even if it is a tangible reality every three years, when the Awards are given, and even if smaller groups from the club meet occasionally, it is less a club than a self-generated network.

It arose out of a vision formulated by the Aga Khan because of his concern about the quality of the environment in Muslim lands during the early seventies.

It grew, then, out of its own activities, at times for bureaucratic reasons, at other times because of the questions it was raising.

The main reason for its achievement, however it is to be judged from the outside, is that its mission is unique, but, even more so, because the range and qualities of its activities and especially of the people who have devoted themselves to its continuing operation are of an order hitherto unknown in this century.

I shall first turn to the character of the mission and then of the people committed to it.

There are two ways to define that mission. One is to return to the speeches and other public statements which accompanied the first Awards in 1980 and to the many papers which can be found in the proceedings of the seminars sponsored by the Aga Khan Award, in the earlier books dedicated to cycles of Awards, or in the interviews with His Highness Karim Aga Khan published over the past sixteen years or so.

From all these documents the sense of a mission does indeed emerge: to incorporate and understand the astounding wealth of fourteen hundred years of an Islamic architecture built, mostly by Muslims, for their Muslim brothers and sisters and for all of those who lived in lands ruled by Muslims, to escape from the constricting bland ness of external, and mostly western, imports; to look with care, intelligence and affection at the traditional structures of the environments in which Muslims live now and have lived in the past;

to find ways to adapt these structures to the contemporary world, while forming new generations of men and women ready to meet on their own the challenges of the present and, by extension, of the future and to respond to the aesthetic, if not the technological, presence of the West.

Today these words and the thoughts they imply as well as the emotions which led to them are no longer as original as they were fifteen or sixteen years ago.

Partly through the efforts and activities of the Aga Khan Award, notions of architectural identity, of reliance on native rather than imported practices and talents, of an ideologically significant rather than merely antiquarian past, of technologies appropriate to each task, of new partnerships

between decision making and execution of pride in the accomplishments of the past of the lands on which one builds, of locally inspired rather than imported educational objectives in professional schools, have become standard statements in political and educational discourses everywhere.

Results may not have always coincided with expectations, but it takes time for habits to change.

Yet, in theory and often in practice, considerable progress has been achieved in establishing local or regional norms for architecture, in developing critical thinking at nearly every level of planning and construction, in training young professionals to have a greater sensitivity to their past than they had previously, and in planning or designing successful works of architecture, or environmental projects in all forty-four of the world’s countries with predominantly Muslim inhabitants.

In a very practical sense, the mission or a mission has been accomplished. All that may be needed is to continue and to refine these new habits as new challenges and new needs creep up.

Yet, there is another way of defining that mission than by listing organisational, educational, or even creative objectives and then measuring them against accomplishments.

For the cultural and political phenomena which created the

To read more about the Architecture For Islamic Societies Today book Click the download button below to get it for free

or

Report broken link

Support this Website

for websites