| Reframing The Alhambra Architecture |

| Olga Bush |

| 337 |

| |

| PDF Direct Download Link |

| Click for Hard Copy from Amazon |

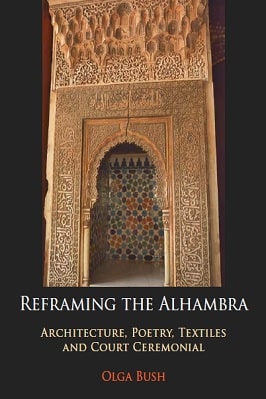

Reframing the Alhambra

Reframing the Alhambra

Architecture, Poetry, Textiles and Court Ceremonial By Olga Bush

REFRAMING THE ALHAMBRA

Book’s Introduction

In the summer of 1832, the youngest son of Ferdinand VII of Spain (r. 1808 and 1813–33), the infante Francisco de Paula, and his wife Luisa Carlota, made a visit to Granada, and, following hasty efforts to rehabilitate some of the dilapidated precincts, they were lavishly celebrated in the palaces of the Alhambra on the Sabika hill over- looking the city (Figure I.1).1

It was almost precisely 340 years since the Catholic Monarchs Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon (r. 1474–1516) had taken possession of the Alhambra on 1 January 1492 as a sign of the final defeat of the Nasrids (r. 636–897/1237– 1492), the last Muslim dynasty in Iberia.

More immediately, it was nearly two decades since Napoleon had been forced to withdraw from Spain and Ferdinand VII was restored to the throne in 1813.

For the French troops, the Alhambra had been little more than a bar- racks, and an explosion of their munitions had done great damage to the site, adding injury to the insult of the occupation.

The festivities for Francisco de Paula and Luisa Carlota represented a reassertion of the centuries-old claims of royal patrimony, and a reaffirmation of the legitimacy of the Spanish dynasty and its political control over the whole of the national territory.

And even now, in democratic Spain, each year on 1 January, the city of Granada continues to celebrate the toma, that is, the taking of the Alhambra, a site of memory of national identity, still defined in part against the shadow of the Islamic past of al-Andalus, or medieval Muslim Iberia.2

In the same year, 1832, American writer Washington Irving (1783–1859) published The Tales of the Alhambra simultaneously in England, France and the United States.3

Irving had resided in the Alhambra in the spring of 1829 and he recorded both his impressions and his fantasies in his tales of a place that he found to be ‘imbued with a feeling for the historical and poetical, so inseparably intertwined in the annals of romantic Spain’.4

The book is still on sale in the Alhambra and throughout Granada in editions in many languages, as an enduring expression of the Orientalising imagination.

Taken together, the visit of the royal family and the publication of The Tales in 1832 – an embodiment of real sovereign power and its oblique reflection in romanticised fiction – mark the character of what might be called the modern Alhambra, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984 that now attracts over 8,000 visitors daily.5

Irving was not wrong in saying that the historical and poetical – and one may add the aesthetic and commercial – have been inter- twined in the modern Alhambra.

Among the many visiting artists who drew the palaces as early as the 1770s, the British architect Owen Jones (1809–74) is the pre-eminent figure at that crux.

In contrast to the Orientalist artists of the Romantic period, who rendered palatial ruins to evoke the aura of the exotic past, Jones executed scrupulous on-site studies of the architecture and its decoration in 1834 and again in 1837.

His historical appreciation of the Alhambra was reflected through his widely disseminated publications of 1842–45 and 1856.6 On the other hand, Jones’ experimentation with materials and modes for reproducing historical architecture and the practical application of his colour theory led to his design of the ‘Alhambra Court’ in the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, England in 1854, which made him a leading contributor to the fabrication of Alhambresque simulacra.

The Alhambra became a major point of reference for Orientalist architecture in the United States, Europe – and even Egypt! – from palaces, hotels and banks to granaries and railway stations, movie theatres and synagogues.

The thrust of contemporary scholarship, dating back to the foundational work of Leopoldo Torres Balbás (1888–1960) during his tenure as preservation architect of the Alhambra from 1923 until 1936, has been to strip away the poetical, in Irving’s sense – always a projection deeply inflected by European colonialism – and to restore a clearer view and better understanding of the historical Alhambra.

In the briefest of outlines, this is what is known about its development.

The first Muslim dynasty in Iberia, the Umayyads (r. 92–423/ 711–1031), had their seat of power in Córdoba, but built a fortress on the SabÈka hill in Granada, as one of many defensive strongholds in their widespread dominions.

The Umayyad fortress was known as al-qala al-˙amrå or the red castle (al-Óamrå or the Red) already in the third/ninth century, referring to the colour of the clay used in its constructions.

After the breakup of the Umayyad caliphate into petty kingdoms during the mulËk al-†awåif or taifa period (423– 79/1031–86), the fortress was enlarged by the local ZÈrid dynasty (r. 403– 83/1013–90).

It was the Nasrids, however, who created the palatial city that came to occupy the entire crown of the SabÈka hill, measuring 740 m × 220 m, an architectural complex whose majestic silhouette stands out against the backdrop of the mountains of the Sierra Nevada (Figures I.2–I.4).

First, they erected a new fortress (al-qaßaba) on the foundations of the earlier fortifications at the west end of the escarpment. The royal madÈna, or city, then extended eastward, comprising buildings for the court administra- tion, palaces with courtyards, pools and gardens, a congregational mosque, oratories, baths, a royal cemetery and, at the east end of the hilltop, the industrial zone that encompassed the royal work- shops for the production of luxury goods for the consumption of the court.

Two main streets running in the east–west direction and secondary streets between them provided communications among the different parts of the Alhambra.

A complex irrigation system supplied the water necessary for the daily functions of the city, including the cultivation of orchards.

The palatial city was enclosed by a curtain wall with both upper and lower sentry walks that reached to the fortress on the west, forming a well-integrated defensive system.

In fact, the Nasrid Alhambra was never taken by storm. The numerous, massive towers and gates overlook the steep slopes of the hill, the city of Granada and the surrounding landscape.

The Nasrid Alhambra developed gradually over the course of the two and a half centuries of the dynasty’s reign, serving as the centre of its military and political power in the kingdom of Granada.7 The architectural projects initiated by the first sultans

To read more about the Reframing The Alhambra Architecture book Click the download button below to get it for free

or

Report broken link

Support this Website

for websites