| Servants Of Allah By Sylviane A Diouf |

| Sylviane A Diouf |

| 339 |

| |

| PDF Direct Download Link |

| Click for Hard Copy from Amazon |

SERVANTS OF ALLAH -Book Sample

Introduction- SERVANTS OF ALLAH

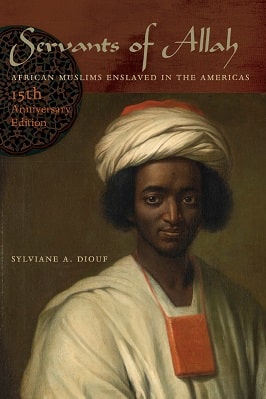

In 1998, when Servants of Allah was first published, I could not have imagined that I would be writing a new introduction to the volume fifteen years later.

Three years earlier, I could not even imagine this book would ever exist. I had started writing it in French, certain I would find a receptive publisher in Paris. Only when, to my utter surprise, no one shared my enthusiasm—to say the least

—did I decide to start all over. Fifteen years later, Servants of Allah is still here, and Allah’in Kullari—its Turkish version—has gone into two editions. As for Serviteurs d’Allah, it has yet to exist; nothing has changed there.

But change there has been, and plenty of it, between 1998, the end of the twentieth century, and today, roughly a decade and a half into the twenty-first. A new political, religious, and social reality unexpectedly transformed a book on a hitherto obscure part of slavery history into what its publisher has deemed “a surprise bestseller.” Sadly, it took a tragedy to alter the landscape, literally and figuratively.

In the aftershock of 9/11, against all expectations, an authentic interest in Islam and Muslims manifested itself. Community centers, churches, schools, universities, libraries, museums, and international organizations solicited scholars, religious figures, and ordinary believers asking for information, explanations, and responses to fear and incomprehension. Servants of Allah, along with other scholarship on Islam, Muslims, American Muslims, and Muslims in America became an integral part of this process, especially as it made clear that Islam and Muslims were not recent arrivals but had been part of the American fabric from its very beginning. The realization that Islam had deep roots in the United States was often a stunning discovery to non-Muslims and Muslims alike. That Islam was brought not only to the United States but also to the entire Western Hemisphere, from Cuba to Peru and from Guadeloupe to Guyana, and had been maintained by enslaved Africans was nothing short of mystifying for most people. That these Africans had written documents in Arabic was a fact that shattered ingrained stereotypes.

There was a genuine interest in the history in and of itself, but there was also a larger narrative into which it fit. The book appealed to the voices that sought to bring or reinforce ecumenism, tolerance, and fraternity among peoples of various

faiths at a time when these qualities were in short supply. By putting Islam in an hemispheric context since the early 1500s, it showed that Islam was the second monotheist religion introduced into all parts of the New World—after Catholicism and before Judaism and Protestantism—thus exposing its longevity, its continental reach, and its followers’ resilience even under the worst circumstances. In the face of mounting suspicion of foreignness and supposed anti-Americanism, Muslims were eager to demonstrate that Islam was as much an American religion as any, one that had coexisted with others quietly for centuries and whose followers had contributed to the development of the country. Perhaps more than anything else, at that moment, it was this mainstreaming of Islam and Muslims that attracted those who found themselves on the defensive, asked to demonstrate their “Americanness.”

But there was still another dynamic going on within the Muslim community itself. Many Muslims who embraced the centuries-old history of Islam in the Americas as their heritage were not of West African descent. White and Hispanic Americans and men and women whose roots were in the Middle East and Asia were quick to claim West African Muslims as their brothers and sisters in faith, although some—by no means all—among them had failed to acknowledge sub- Saharan Africa as a land of Islam, had ignored African Muslims, and had shown no previous interest in African American history. Yet they now proclaimed their connection to the people and the history.

West African Muslims enthusiastically welcomed a historical narrative they could relate to. The events, religious and political figures, and celebrated places of learning from Almami Abdul Kader Kane and Usman dan Fodio to the Qadiriyya, Pir, and Timbuktu were already familiar, but placed in an American- wide historical perspective, they took on an all-new dimension.

African American Muslims, who often complained of being marginalized by their coreligionists for being converts—even when they were second-or third- generation Muslims—and supposed heirs to home-grown proto-American Islamic movements considered blasphemous by orthodox Islam, embraced the history of African Islam in the Americas as their own. It became proof of their legitimacy and ancient lineage as Muslims. For generations, the Black Church had been seen as the historical religious foundation of African Americans, but Islam complicated the narrative. Muslims could assert an even earlier religious heritage, and it was one that, unlike Protestantism, had its roots in Africa.

Granted there were some Catholics among the West Central Africans who had been deported to the Americas, but Islam had been implanted in sub-Saharan Africa at least five centuries before the Portuguese sent missionaries to Kongo.

Surprisingly, as non–African American Muslims had been quick to embrace the story and make it their own, many African American non-Muslims at the time did not appropriate a narrative that was clearly their own and filled gaps in their history. Asked why, they often responded that they did not perceive it so much as African and African Diasporan history but rather as Muslim history, and therefore they did not feel any particular connection to it.

Over the past few years, the social, political, and religious climate has changed once again, tremendously. Muslims, Islam, “Jihadi terrorism,” and the “war on terror” have been relentlessly in the news and have become embedded in our daily life in ways that were once unthinkable. There is a climate of “Muslim fatigue” among many people, of Islamophobia among others, but there is also continuing interest. Until 2001, Muslims were for the most part little visible, hence the curiosity following 9/11. But today, precisely because “they”—and the conflation of some and most is unfortunately readily done—are omnipresent and highly visible, the attention has not abated. Non-Muslims interested in the topic seek to know more about a religion and its followers who so dominate the news cycle and the global political landscape. Muslims themselves, for a variety of reasons, have been looking for more knowledge about their faith and its international history.

Thus, although times have changed, the interest is still there, and research on African Muslims during slavery continues, albeit in a quite different environment. When I wrote Servants of Allah so many years ago, it was not because I knew something but because I wanted to know. I wrote the book to find answers to my questions.

The absence, the invisibility of the Muslims in the hundreds of books on slavery I had read over the years, was perplexing. Since they lived in areas that had been involved in the transatlantic slave trade and the ethnic groups they belonged to were listed in the numerous tables historians had compiled, why did they disappear as Muslims? How could the religious dimension, an essential part of people’s lives and identity, simply vanish once Africans had reached the Americas? The question, or rather the absence of response, was all the more bewildering as a whole segment of academic research had been devoted to showing that African religions had not disappeared in the New World. Obviously, then, only Islam had evaporated and had done so immediately. I was familiar with the Brazilian Muslims since I had read Pierre Verger’s seminal and illuminating Flux et reflux de la traite des nègres entre le Golfe de Bénin et Bahia de todos os Santos, du XVIIe au XIXe siècle (published as Trade Relations between the Bight of Benin and Bahia from the 17th to 19th

Century by Ibadan University Press in 1976).1 They had remained Muslims, created vigorous communities, organized conspiracies, and launched a major revolt. Why would the Muslims have survived as Muslims only in Brazil? What had happened to the others? How could their faith have manifested itself even if not in such an obvious manner? As a descendant of Amar Khaly Fall, the founder, in 1611, of the Islamic university of Pir in Senegal, I also had questions about the fate of their literacy and the manuscripts they could have produced.

My interest was not limited to a particular area. I wanted to unearth stories not from just one country but from all over the Americas to get a better picture of Muslims’ place in the Diaspora. The search brought more interrogations but also answered more questions than I initially had. I uncovered a world whose many parts had never been brought together, and it was an exciting discovery. Thus, by design, Servants of Allah had a very large scope and time frame: the Western Hemisphere and the entirety of the slavery period.

For the United States, the studies of African Muslims that had preceded this book consisted of the biographies of two individuals—Ayuba Suleyman Diallo (Job ben Solomon) and Ibrahima abd al Rahman. More broadly, Allan D. Austin’s 1984 sourcebook had gathered documentation on Muslims in Jamaica and the United States; and several scholars had, since the early 1900s, focused on Muslims in Brazil.2 All these studies had brought forth invaluable information. However, Muslims appeared as in silos, their particular stories unconnected, which made them and their experience appear exceptional.

It could well have been proposed that only a few Muslims were transported to a handful of Western countries or that only a small minority remained Muslims. A hemispheric approach was needed to provide a large framework that connected glimpses of lives and fragments of stories scattered over three continents into one narrative that could reveal a previously hidden dimension of African history, diasporan history, and Muslim history. This perspective helped recover, as Timothy W. Marr has stressed, “lost dimensions of both the diasporic history of Africans in the Americas and the religious beliefs and practices of enslaved Americans.”3

With the exploitation of sources from Antigua, the Bahamas, Belize, Brazil, Carriacou, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Panama, Peru, Saint Croix, Tobago, Trinidad, and the United States, Servants of Allah established the widespread presence of African Muslims in the Western Hemisphere. But more importantly, it revealed the upholding and the manifestations of the religion on a large scale. This first broad observation of a historical reality that had not received any attention

before evidenced the fact that Islam was indeed a diasporic religion whose expressions were widespread, distinctive, visible, and recognizable enough to be recorded in a variety of written sources and commented on by colonists and travelers throughout the Americas. Through these observations and other materials, it became clear that Muslims could no longer be envisioned as isolated, idiosyncratic individuals or small groups but rather must be seen as an extensive population, as much part of the ummah—the world community of Muslims—as any, whose commonality was not based on ethnicity, language, or shared geographic origin but on religion. It also signified that seen from that angle, even though Muslims were a minority in the Americas, they were a significant one among Africans whose religions were based on ethnicity.

Moreover, the hemispheric perspective showed that there was a Muslim continuity, a Muslim way of behaving, dressing, rejecting conversion or becoming pseudo-converts, and expressing one’s faith, for example, that manifested itself across European political, religious, and linguistic boundaries.

This new approach revealed fresh possibilities of scholarship. It helped expand the scope of study of African peoples’ religions beyond the obvious. It enabled scholars to move outside of the traditional way of studying Africana religions, which is to focus on the Black Church in the United States and African-derived religions in the rest of the hemisphere: Candomble in Brazil, Santeria in Cuba, and Vodun in Haiti, for example. The fact that there was a religion that had preceded them all and was practiced on Virginian farms and Cuban plantations, in Peruvian cities and Jamaican towns could no longer be ignored and had to be studied in a systematic manner with the appropriate tools.

As much as Muslims in the Americas were part of the ummah, they were also part of the enslaved world, and non-Muslims not only were well aware of their presence but were sometimes influenced by Islam and its followers. The work which Servants of Allah began of revisiting the neo-African and African-derived religions continues to be imperative, as some have been shown to have integrated into their liturgy Arabic vocabulary, specific Muslim rituals, and the acknowledgment of Muslims themselves. By the same token, the wide-scale Muslim dimension forces us to reassess the issue of “African retentions” in all aspects of the African diaspora’s culture, as some elements are clearly and indisputably Islamic, while others are more hidden.

As shown in this book, Muslims’ literacy, a distinctive feature, also reshapes the discussion about “slave narratives.” This literacy enabled the creation of written sources by the Africans themselves on a much wider scale and covering more genres than what was produced by the few people who wrote in European

languages, such as Phyllis Wheatley and Olaudah Equiano. Muslims’ production was not restricted to a handful of individuals writing for a Western audience but involved thousands of Africans scattered across the New World, writing primarily for their own. Theirs was a completely different exercise, which— when properly translated and interpreted—provides new understanding of their intellectual, social, and religious lives, their educational attainments prior to deportation, and their personal and collective perspectives. Moreover, their writings evidence or hint at efforts at keeping the community “on the right path,” at preserving orthodoxy, and at extolling the value of education, self-discipline, and literacy.

A large scope shows the diversity and commonalities of Muslims’ written output. A narrow focus on the United States would have yielded a limited number of manuscripts and records of no longer extant documents: an autobiography and letters by Omar ibn Said, a letter (not recovered) by Ayuba Suleyman Diallo, a short religious piece by Bilali Mohamed, and simple writings on demand by Ibrahima abd al Rahman and Charno. But when other parts of the Americas are taken into account, a much wider range of literature comes to light: autobiographical sketches, religious texts of various types, Qur’ans, plans for revolt, talismans, personal letters, letters to the authorities, and official petitions.

These various documents were written not only in Arabic but also in mixed Arabic/ajami (any language written in Arabic script). What this perspective provides us is the understanding that particular types of texts that have not been found in one specific place probably existed nevertheless but disappeared just like the rest of the Africans’ meager possessions. For example, given the extensive use of protective talismans by Sufis in Africa (and elsewhere), it would be hard to imagine that they did not survive in the Americas. Evidence from Brazil, Cuba, and Saint-Domingue, for example, shows that they did, and there is no cogent reason why they would not have existed in other parts of the hemisphere. Therefore their absence in, say, South Carolina, does not mean Muslims had somehow decided to give them up or that not one man capable of making them (including charlatans) had ever landed in Charleston but rather that they have been lost or that some may still be found. The variety of documents that have come to light also evidences the range of skills and knowledge that Muslims brought with them. Some people could read but not write, others were semiliterate, and still others were well educated. John Hunwick has noted that Omar ibn Said “had not reached such heights as would have made him into a scholar in his own right. He was literate but not learned.”4

In contrast, the analysis of a number of documents by Nikolay Dobronravin

of St. Petersburg State University has revealed the high level of erudition of some Muslims.5 Quotations from Qasidat al-Burda—an ode of praise for the Prophet Muhammad—by the eminent thirteenth-century Egyptian Sufial-Busiri and from the Maqamat Al-Hariri, a collection of fifty short stories written by Abu Muhammad al Qasim ibn Ali al-Hariri (1054–1122) of Basra, Iraq, evidence the degree of scholarship of some enslaved West African Muslims.

Besides diversity, there is also commonality. All extant manuscripts are Muslim specific. In other words, even when they are not religious texts, they refer to Islam and to the writers being Muslims, and they contain surahs, prayers, and Arabic salutations. Clearly, their religious identity was central, essential to Muslims. It could not be dissociated from who they were and what they did.

The story of the African Muslims also allows us to go beyond the creolization model, defined schematically as the mixing of cultures (including religion) and languages in the early colonial world. In many ways, Muslims, because of the exigency of their religion, strove to remain outside of, not mix with, the cultural and religious models imposed by the West and Christianity. This inclination showed, whenever possible, in their dress, physical appearance, and diet, in the establishment of underground Qur’anic schools, in the continued writing of Islamic texts and even Qur’ans, in the retention of their names, and in their efforts to go back to Africa. As Paul E. Lovejoy has stressed, “Muslims demonstrated that the range of cultural adjustments possible for slaves was much more complex than has often been supposed.”6

The study of enslaved Muslims thus contributes to advancing scholarship in a number of disciplines and themes. However, in the first edition of Servants of Allah, I deplored the lack of interest in such research especially in the United States, where more studies on slavery have been produced than anywhere else in the Americas.

Lack of resources cannot explain this oversight because of the existence of published records on eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Muslims.

Additional material was made available in the early twentieth century. W. E. B. Du Bois had mentioned the Muslims of Bahia and their 1835 revolt—strangely enough he thought “they attempted to enthrone a queen”—in 1915.7 The reminiscences of formerly enslaved men and women in Georgia describing the behavior of their grandparents, who could be readily identified as Muslims, had been published by the Works Progress Administration in 1940, and the Journal of Negro History had put out the first study of the Ben-Ali Diary that same year. Lorenzo Turner’s book on Gullah, published in 1949, evidenced a number of Islamic names in vogue in the Sea Islands. By the end of the 1960s, Philip Curtin had edited Africa Remembered, which presented information on and biographies

of Ayuba Suleyman Diallo (enslaved in Maryland), Salih Bilali (Georgia), and Abu Bakr al Siddiq (Jamaica). In 1968, Douglas Grant had published The Fortunate Slave: An Illustration of African Slavery in the Early Eighteenth Century, about Ayuba Suleyman Diallo. Newbell Puckett’s research had produced a list of hundreds of African names, many of them distinctly Islamic.8 The 1977 biography of Ibrahima abd al Rahman “fell into an academic black hole,” stressed the author, who remained “mystified by the cold shoulder that the academic world gave the book.” And Allan Austin’s work did not generate the interest it deserved, let alone new research, either.9

Writers and artists for their part gave the subject scant attention. Alex Haley did not make Islam a meaningful element of his ancestor’s life, as it most probably was, and did not mention the existence of other Muslims in Roots. Toni Morrison’s 1977 Song of Solomon contains the verses,

Solomon and Ryna Belali Shalut Yaruba Medina Muhammet too. Nestor Kalina Saraka cake,

with no explanation and no other reference to Muslims.10 Strangely, this recitation of the names of a Muslim family on Sapelo Island, Georgia, and other allusions to Islam and Muslims are woven into a song created by Morrison, who set her story in Virginia. Although Julie Dash’s 1991 movie Daughters of the Dust opens with the praying of an elderly Muslim, an overt acknowledgment of the Muslims of the Sea Islands, it does not pursue their story any further. Steven Spielberg’s 1997 Amistad features—for a second—a few Muslims praying on the ship deck; but at no point is there any allusion to the prisoners’ religions except when it comes to the Christian convert. There were Muslims on the Amistad, as has been documented by Richard Madden, who testified on their behalf in Connecticut on November 11, 1839. He

spoke with one of them and repeated in the Arabic language a Mohammedan form of prayer and the words “Allah Akbar” or “God is Great” were immediately recognized by the negro, and some of the words of the said prayer were repeated after him by the negro. That deponent addressed another negro, standing by the former, in the ordinary terms of oriental salutation “salaam Aleikoum” or Peace to you and the man immediately replied “Aleikoum Salaam” or with you be peace.11

One of the young men on board, Ba-u, said that his father was a marabout

(learned man).

Considering the number of books on various aspects of slavery published in the United States in the past thirty years, research on Muslims is thus strikingly limited. Part of the issue may be that a focus on Christianity has obscured the existence and role played by other religions. To overstate Christianity’s dominance before emancipation minimizes or plainly ignores the diversity of the enslaved community’s religious experiences. Moreover, continuing a line of thought started in the nineteenth century, some scholars (and others) appear to perceive that Islam is not an “African religion” and that there is therefore no reason to include African Muslims in works on African and diasporan religions.

The African Muslims’ culture and religion are viewed as foreign, Arab. Islamic influence is thus wrongly perceived as Arabization. Interestingly, Chinese, Indian, or Albanian Muslims are not seen as being Arabized; only sub-Saharans are deemed acculturated, which would seem to indicate a particular bias on the part of the people making these statements. To acknowledge the centrality of Islam to African Muslims, in Africa and in the New World, is perceived as belittling what some believe are authentic African cultures and religions.

Thus, to celebrate the so-called real Africa or what is supposed to be the real Africa, Islam and Muslims have to be denied or minimized. In a mythical reconstruction of African cultures as static, millennial, untouched, and uninfluenced, Islam has no place.

Today, although enslaved African Muslims have generated much interest in the larger public, the subject matter, in the United States, has not spawned breakthrough academic research. Only a few articles and two new books have been published in the past decade and a half. Another two publications concern new analysis and/or translation of previously published works. Straddling West Africa, Brazil, and the United States, a new annotated edition of the biography of Mahommah Baquaqua was published in 2001, with a revised, expanded version appearing in 2007. In The Biography of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua: His Passage from Slavery to Freedom in Africa and America, Paul E. Lovejoy and Robin Law have pinpointed Baquaqua’s hometown, “Zoogoo, in the Interior of Africa,” as Djougou in northwest Benin, three hundred miles from the coast.

Based on a careful reading of the text, they have argued that the “biography” is a composite, more autobiography than was previously assumed. They have also ascertained the consistency of Baquaqua’s description of his life in Benin with what is known about the political, cultural, and social history of the region at the time, thereby authenticating the text as reflecting the genuine experience of a deported African. In 2011, Ala Alryyes offered a new translation and

interpretation of Omar ibn Said’s autobiography that evidences the subtle manner in which the author denounced his enslavement and affirmed his Islamic faith.12

As was the case earlier, Brazil has led the way; research there is still significantly ahead of that of any other country. The rich corpus of documents written in Arabic and ajami that does not exist elsewhere (or has not been discovered yet) is being constantly mined, and archival research in Brazil and West Africa has brought forth the personal stories of hitherto unknown individuals.

Following the 1993 English edition of João José Reis’s 1986 Rebelião escrava no Brasil: A história do levante dos malês em 1835, under the title Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia, a revised and expanded version was published in Brazil in 2003. In this voluminous book, and in an essay in 2004, Reis reinterprets the 1835 uprising as a Muslim Nago (Yoruba) movement rather than a larger African Muslim one.13 On the other hand, José Antonio Cairus, in an article in the Brazilian journal Topoi, defends the jihad theory of the revolt.14

Reis also published, with Flávio dos Santos Gomes and Marcus J. M. de Carvalho, the fascinating story of the Yoruba Rufino, born in Oyo, enslaved in Salvador—where he arrived in 1823—and later in Rio Grande do Sul. Rufino bought his freedom in 1835 and moved to Rio before embarking as a cook and merchant on slave ships sailing to Angola during the illegal slave trade.15 After the ship he was working on was seized, Rufino was sent to Sierra Leone, where he attended Qur’anic and Arabic classes. Sent back to Pernambuco, he later returned to Sierra Leone to continue his religious education. He moved back to Brazil, where he established himself as a marabout/diviner with a multiracial clientele and became a leader of the African Muslim community. Rufino was arrested in Pernambuco in 1853—as word spread of a potential slave revolt; he was found with a great quantity of books and writings, some brought back from Sierra Leone. He was released two weeks later. As the authors conclude, “His story is even more extraordinary because of his experience as a worker in the slave trade; he was a Muslim who, unlike other Muslims enslaved in the Americas who managed to return to Africa to stay, went to Africa to improve religious training, and returned to live the rest of his life in the land where he had once served as a slave.”16 Lisa Earl Castillo has retraced the absorbing story of three Yoruba of Bahia (one was a woman) who returned to Africa in 1836 and settled in Benin and Togo.17 They were all slave owners (holding from fourteen to forty-five individuals, many of whom they emancipated), one was a Muslim,

and another traveled in Muslim circles.

Nikolay Dobronravin has worked on several manuscripts and brought to light an array of previously unknown information.18 His translation of the moving letter—in Hausa and Arabic—of a man announcing the death of his newborn daughter, Fatumata, to a religious leader, Malam Sani, reveals the personal side of the Muslims’ literacy. It also evidences, once more, the Muslims’ use of ajami and the Sufi affiliation of the writer, Abdul Qadiri, who evidently belonged to the Qadiriyya tariqa (the order founded by the eleventh-century Iranian Abdul- Qader Gilani).

Another piece analyzed by Dobronravin is a Muslim calendar found in Salvador. It includes the names of days and months written in a phonetic way: Yorubaized Arabic. Other fascinating manuscripts studied by Dobronravin include a 120-page prayer book found around the neck of a dead insurgent in Salvador and a book confiscated from a Mina group by the police in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, several years later. Dobronravin has also published an overview of the major stages in the history of Brazilian Islam and a reinterpretation of its role in the history of Afro-Brazilians. In this article, he also describes the sources for the study of Muslim culture in Bahia since the 1835 revolt and discusses today’s revival of Islam in Brazil.19

Two interesting manuscripts, one from Brazil, the other from Trinidad, have been translated for the first time and contextualized. The first—held in the library of Le Havre in France—is a forty-five-page document found in the pocket of a Muslim killed during the 1835 uprising. Based on the spelling, Dobronravin suggests he was Yoruba. The text contains several surahs and prayers and invocations that show the owner’s affiliation with the Qadiriyya Sufi order. The second manuscript was written on November 21, 1817, in Trinidad by a freedman, presented as an “Arabian priest,” that is, an imam, who served in a British regiment.20 The author, a recaptive named Muhammadu Aishatu (renamed Philip Finlay), later returned to West Africa. He was asked to produce the piece by an assistant surgeon of the 3rd West Indian Regiment. The complex text, which contains prayers and references to the Qur’an and to the Muslim community, is written in Hausa in Arabic script with words and sentences in Pulaar, Mandinka, and Caribbean Creole. It contains admonitions to follow the shari’a, the sunna, the truth, and the Five Pillars of Islam.

The past few years have seen the discovery or recovery of precious primary sources. In 2000, Abd al-Rahman al-Baghdadi’s “Musalliyat al-gharib” (The Foreigner’s Amusement by Wonderful Things), written in Arabic, became available in European languages.21 Its author was, as his name indicates, from Baghdad, and he had been educated in Damascus. He lived in Constantinople

and from there took a steamship to travel to Al-Basra in September 1865, but he ended up in Brazil, where he stayed for more than a year “to teach the Muslims” of Rio, Salvador, and Pernambuco. His detailed descriptions and commentaries illuminate an important period in the life of these communities, thirty years after the 1835 uprising and almost a quarter of a century before emancipation.

One exciting article by Ray Crook, based on the discovery of an estate inventory in Caicos Islands in the Bahamas, has provided new information on Bilali Mohamed of Sapelo Island.22 Crook’s work fills gaps in this famous Muslim’s family history prior to their arrival in Georgia.

An Arabic manuscript held in the Baptist Missionary Society papers of Angus Library at Oxford University was not exactly newly discovered, since it had been referenced in 1976, but it has been translated for the first time and annotated by Yacine Daddi Addoun and Paul Lovejoy.23 The fifty-page document, far from being excerpts from the Qur’an written by a “Young Mandingo Negro” in Jamaica as previously thought, is a treatise on praying emanating from the elderly Muhammad Kaba Saghanughu, also known as Robert Peart, a man who had been baptized a Christian in 1812. The very existence of this text is another proof of the Muslims’ pseudo-conversions; and its content is another example of religious writing and Sufi connection.

There is still much more to discover, analyze, and interpret. Systematically probing the archives to uncover forgotten manuscripts and other documents by and about the African Muslims is an essential task that needs to be conducted in the various repositories of the Americas as well as in France, the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Dutch-speaking territories such as Aruba, Curaçao, and St. Maarten, as well as Suriname, have been neglected, but research there might be rewarding. The Vatican archives, which hold the records of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions that operated in Latin America, may prove useful since Africans, including Muslims, were brought before the courts for “heresy.”

As is evident with the new translations of Omar ibn Said’s autobiography and other documents in Brazil, already known manuscripts need to be retranslated, analyzed, and contextualized. For some of these, essentially the talismans, the assistance of West African marabouts is central. Only they can decipher and uncover hidden meanings. Today, the existence of a corpus of manuscripts from the Bahamas, Brazil, Jamaica, Panama, and the United States offers the possibility of doing a comparative analysis that would reveal their commonalities, if any, and differences and could enlighten us further as to who the Muslims were in Africa and the West. Needless to say, team efforts by

scholars trained in classical Arabic, Qur’anic studies, West African languages, history and practices of Islam in various West African communities, and Sufism are of the essence.

As mentioned earlier, the influence of Islam and Arabic on the rituals and language of other religions is another significant subject worthy of exploration. Servants of Allah has shown some of these connections for Vodun, Palo Monte, and Umbanda; other religions in other countries should be studied as well.

The exploration of Sufism is of singular importance. The most widespread Sufi order in North, West, and East Africa at the time was the Qadiriyya, established in the twelfth century by Abdul-Qader Gilani of Baghdad.

References, explicit and implicit, to this brotherhood and its founder have surfaced in manuscripts in Brazil, Jamaica, and Panama and in the backgrounds of several men in various countries. A thorough examination and analysis of other documents, as well as personal stories, and recorded behavior and terminology should bring additional information as to the manifestation of Islamic mysticism in the New World.

The manuscripts and stories of Abul Keli in the Bahamas and Sheikh “Sana See” in Panama point to new avenues of research in the little-explored world of the recaptives, or Liberated Africans.24 These men and women—some of them Muslims—freed from slave ships after 1807 were relocated in Sierra Leone, St. Helena, and the Caribbean. A list of over ninety-one thousand names culled from the records of the mixed commissions in Sierra Leone and Cuba can be a point of departure.25 For example, the Preciosa, which left Rio Pongo in 1836 and was sent to Havana, had 290 people on board, including men and women whose names identify them as Muslims, such as Fatima, Sori, Brama, Bakary, Mamodi, Mamado, and others.

A topic worth investigating concerns the possible relations between African and Indian Muslims. About 240,000 indentured Indians from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal were transported to Guyana starting in 1838; and 144,000—15 percent of them Muslims—reached Trinidad between 1845 and the early twentieth century. Incidentally, the Fath al-Razak (Victory to Allah the Provider), the first ship to land there, belonged to Ibrahim Bin Yussefa, a Muslim merchant from Bombay.

The existence of “Muslim networks,” mentioned in Servants of Allah, are worthy of further investigation. They extended from West Africa to the Americas and within the New World.

In general, research on African Muslims is being done primarily by historians, and historians’ preferred sources are written documents. This explains partly why the scholarship on Brazil is so advanced: there are numerous texts available for translation, analysis, and interpretation. But manuscripts cannot tell everything; they cannot cover all aspects of the history of Muslim communities. Some areas of research pointed at in Servants of Allah that are better suited to other disciplines such as anthropology, linguistics, folklore, musicology are still little or not explored.

Clearly, we have only scratched the surface, and future research will greatly enrich our knowledge of a unique story that started more than five centuries ago and stretched over 350 years when Muslim men, women, and children were sold in the New World. They were among the very first Africans to be deported and among the last.

Of course, the American story of these Muslims starts in Africa. It has its roots in the aftermath of the dislocation of the Jolof Empire, the politico- religious wars in Futa Toro and Bundu in Senegal, Futa Jallon in Guinea, and in Central Sudan (Northern Nigeria/Chad), as well as other conflicts in north Ghana and Dahomey. It starts in peasant resistance to the raids of the warlords and corrupt monarchies. It emerges with religious men willing to take a chance in a time of insecurity to pursue education far from home and to find the best possible religious guidance. It also has its origins in the riposte of the so-called infidels, who had become a reservoir of captives whom the Muslims sold to the foreign slavers and who, in turn, got rid of their enemies.

In freedom as in enslavement, the Muslims placed their hope in Islam, their strength and their comfort. But for many, Islam and its complex relationship with the multiform slave trades within and out of Africa was also what had brought them in chains to the Western Hemisphere, as the first chapter of this book illustrates.

As Muslims in Christian lands, the involuntary immigrants faced daunting obstacles to maintain and express their faith. Notwithstanding the limits imposed on them by their subordinate status, many succeeded in following the principles of their religion. How they upheld the Five Pillars of Islam in their new world is the subject of chapter 2.

A double minority—religious and ethnic—in the colonial world, as well as an enslaved community, the West African Muslims strove hard to maintain their traditions, values, customs, and identity. At the same time, paradoxically, Islam was one of the engines of upward mobility within the structure of slavery. The

Muslims’ mode of survival, their success in the preservation of their traditions, and their relations with non-Muslim enslaved and enslavers are explored in chapter 3.

Muslims arrived in the Americas with a tradition of Arabic literacy that they struggled to preserve. It set them apart within the enslaved community and vis-à- vis the larger society. Literacy—a distinction and a danger—and its various uses and expressions are discussed in chapter 4.

Well organized and a galvanizing force, Islam was sometimes the catalyst of insubordination. It played a part in some uprisings and was a motivating force that sent freed men and women back to Africa, as is exposed in chapter 5.

Islam’s mark can be found in certain religions, traditions, and artistic creations of the people of African descent. But for all their contributions and accomplishments, the Muslims have largely been ignored. Chapter 6 examines their legacy and ponders their disappearance from collective memory.

Because Islam as maintained by the West Africans did not outlive the men and women who brought it to the New World, one might think that the African Muslims failed, that their story speaks of defeat and subjugation. Through examining their history, their stories, and their legacy, however, this book reveals that what they wrote on the sand of the plantations, in their clandestine Qur’anic schools, and in the secret of their homes is a successful story of strength, resilience, courage, and dignity.

The Muslim Legacy

With a documented presence of five hundred years, Islam was, after Catholicism, the second monotheist religion introduced into the post-1492 Americas. It preceded Lutheranism, Methodism, Baptism, Calvinism, Santeria, Candomble, and Vodun to name a few. All these religions are alive today and are followed by the vast majority of the Africans’ descendants, but not one community currently practices Islam as passed on by preceding African generations.

Islam brought by the enslaved West Africans has not survived. It has left traces; it has contributed to the culture and history of the continents; but its conscious practice is no more. For the religion to endure, it had to grow both vertically, through transmission to the children, and horizontally, through conversion of the “unbelievers.” Both propositions met a number of obstacles.

Barriers to the Vertical Growth of Islam

The transmission of a religion to one’s progeny presupposes, of course, that there is a progeny. Yet the very structure of the slave trade, with the disproportionate importation of men, the physical toll that enslavement took on the Africans, and the selling off of family members, placed tremendous obstacles in the path of the constitution and perpetuation of families.

There was, to begin with, a significant imbalance between the number of African males and females deported from Africa. In the eighteenth century, for example, among the Senegambians, 66 percent were males. The figures for the Central Sudanese are even worse, with about 95 percent men.1 On any given plantation the demographics could be even more slanted, with some planters buying males exclusively when they needed sheer strength and adding a few women over the years for reproductive and domestic purposes. Because of this policy, a large number of African men could not form families.

Language barriers and differences in cultures and religions among the Africans added another layer of difficulty in the finding of a mate. Among the native-born population, the sexual distribution was natural, and the sexes tended to be of equal numbers; but there are indications all over the slave world of a tendency to endogamy, with native-born men and women marrying and living among themselves and the Africans who could doing the same.

For both African and native born, the low fertility rate and the high infant and adult mortality rates were another hindrance to the development of families. And at the end of this obstacle course loomed the ever-present possibility of the sale of family members, which could forever destroy the unit and any possible cultural continuity. Therefore, the chances for a Muslim man to find a Muslim spouse, have children, and keep them long enough to pass on the religion were indeed slim. Muslim women fared better in the first and second parts of this process, but the third was out of their control. If the lives of the well-known Muslims are any indication, about half did not have children. By choice or out of necessity, it appears that Omar ibn Said, Abu Bakr al Siddiq, and Ayuba Suleyman Diallo did not have descendants in the Americas.2

In contrast, Ibrahima abd al Rahman, John Mohamed Bath, Salih Bilali, and Bilali Mohamed did have children. There is no indication that Ibrahima’s children, who had Christian names like their mother’s, were Muslims; but one of Salih Bilali’s sons, named Bilali, apparently was a Muslim and kept alive the female West African tradition of the distribution of rice cakes as an Islamic charity (saraka). He married the daughter of a marabout, but their descendants, who grew up seeing Muslims around, nevertheless had no understanding of Islam, at least as recorded by the WPA. In general, the grandchildren of Muslims recalled the exterior manifestations of Islam, such as prayers, but do not seem to have had precise ideas about the religion and, as far as can be ascertained by the published interviews, did not mention the religion by its name. It is not impossible that they knew more about Islam and the Muslims than they revealed but did not wish to confide in white Christian strangers—some of whom were the grandchildren of former slaveholders—asking them personal questions in Jim Crow South.

For the Muslims who had children, conformism on the children’s part and difficulties with literacy may have coincided to prevent the passage of Islam from generation to generation. As a minority religion, Islam was surrounded by religions with a much larger following that may have been more appealing to youngsters in search of conformity and a sense of belonging. To be a Muslim was to singularize one’s self. Moreover, it was an austere religion that manifested itself through rigorous prayers and additional privations, propositions that may have handicapped its acceptance by a second and a third generation.

The lack of interest of the youngsters in the religion of their parents, who had gone to great lengths to preserve it, was deplored by the Muslim clerics of Trinidad. A religious leader regretted that their youngsters “were in danger of being drawn away by the evil practices of the Christians.”3 The laments were the same in Bahia, where the clerics complained of the ungratefulness of the children who turned to “fetishism,” Candomble, or Catholicism.4 After the repression of 1835, the malés became extremely discreet, private, and secretive, and this forced isolation was probably not appealing to the younger generations.

In Bahia, al-Baghdadi noted in 1865, “The majority of Muslim children turn out to be Christians because as they come to this world, they see the festivals of the Christians in the churches, with the abundance of patriarchs, clergymen, music, the beauty of dances. The child sees that only his father is different. He thinks that his father is a liar and joins the majority.”5 And if the passing on of Islam was difficult when both parents were Muslims, it must have proved an even more daunting task to the Muslim who had a non-Muslim spouse.

In addition, as much as literacy in Arabic was a force and an anchor for the faith, it was also most likely a hindrance to its propagation in the particular circumstances of American slavery. African children were educated in Islam through the Qur’anic schools, which were much more than the Sunday schools of the Christians. Islam demanded study and dedication on the part of the children every day of the year, for many years.

In the Americas, the most parents could do was to teach their children in an informal way or, where possible, send them to the more elaborate secret schools that functioned in some urban settings. Further, it is one thing to maintain one’s literacy in Arabic, but it is quite another to acquire it from scratch in the absence of time, adequate structures, and tools, as was true in most cases. Even if a book or Qur’an in Arabic was available, doubtless an enslaved child could not have found the amount of time necessary to learn how to read it.

The only alternative Muslim parents had to teaching Arabic and the Qur’an through schools and written media was to pass on orally what they knew. This mode of transmission works for Christians because images, icons, statues, woodcarvings, stained glass, and wall paintings act as support and explanation. They are the illiterates’ books. But iconography does not exist in Islam.

Whatever was passed on may have been close enough to orthodoxy for the second generation, but by the third, the risks of approximation and misinterpretation would have been high and finding a reference person difficult.

With the definitive end of the transatlantic slave trade by the late 1860s and the passing away of the African-born population, the number of people who could actually read and write Arabic, who were knowledgeable in the religion and could interpret it for the novices, was very much reduced. With some variation in time depending on the country, by the first or second decade of the twentieth century, there were no more African Muslims who could read and write Arabic in the Americas.

Barriers to the Horizontal Growth of Islam

If passing on their “religion of the Book” to their progeny was an arduous task for the Muslims, then spreading the faith among their companions proved equally daunting, if the Muslims even tried. In Africa, proselytizing was mostly done through example, by the mystic Sufis, the merchants, and the teachers who settled among the “infidels.” Active recruiting was usually not part of their activities. Proselytizing in the Americas would certainly have followed the same unobtrusive pattern, only it would have met with more difficulty, because while Africans from different parts of the continent shared the same fate in the Americas, their customs, education, and culture were alien to one another. Their languages were mutually unintelligible and their mastery of the colonial languages only acquired over time.

To hold religious discussions and to successfully convert under those conditions would have been improbable. The Central Africans had had no contact with Islam in Africa, and their linguistic and cultural differences with the West African Muslims in the Americas may have been an insurmountable barrier. The West Africans constituted a group that might have represented a source of potential recruits, as they had already been in contact with Islam in their homeland. But those who had refused conversion in Africa were probably not likely to change their minds in the Americas, particularly if they had been sold by Muslims.

Some proselytizing did occur, as the cultural make-up of the men and women condemned for the 1835 uprising in Bahia seems to indicate. Some Central and West Africans who were certainly not Muslims in Africa took part in the revolt and may have been converts. Undoubtedly there were some conversions, but indications are strong that conversion was far from being a priority for the Muslims. It is remarkable that among the thousands of slave testimonies recorded in the United States, there is nothing but silence concerning the Muslims: no description of their particular rituals, comments about their habits, mention of their religion or of their eagerness to share it.

When references to Islamic rituals emerge, as in the Sea Islands interviews, the believers are said to have been praying to the sun and the moon. The practitioners of Islam obviously had not told their non-Muslim companions who reported these observations anything about the religion. Charles Ball noticed this lack of communication: “I knew several,” he wrote about the Africans, “who must have been, from what I have since learned, Mohamedans; though at that time, I had never heard of the religion of Mohamed.”6 Clearly, the “Mohamedans” he knew were not involved in proselytizing. Ball talked at length with one, “the man who prayed five times a day,” but at no point in the narrative did the Muslim mention the particulars of his religion, which is never quoted by name. Given Ball’s precise descriptions of the Africans’ state of mind, in which traces of Islamic philosophy concerning life and death can be detected, he must have had extensive talks with more than one Muslim. Yet none, not even his own grandfather, tried to impress his religion on him. Nor is there any indication that Salih Bilali, Ibrahima abd al Rahman, and Bilali Mohamed, for example, were involved in proselytizing. Preserving their faith, respecting its exigencies, maintaining a religious community, and trying to pass on their beliefs and knowledge to their children must have proved challenging and absorbing enough to the Muslims, who may have preferred to devote their time, resources, and energy to these tasks rather than to getting involved in missionary work. Reaction to external forces, such as fear of retribution from slave owners, who would not have accepted seeing Islam spread, may also have played a role.

Islam survived in the Americas due to the continuous arrival of Africans— including the recaptives and the indentured laborers after the abolition of slavery in the British and French islands—and not to conversion. There was thus little opportunity for its “creolization.” Unorthodoxy and tolerance of foreign elements, in contrast, are characteristic of the successful African religions that are still alive today. They became creolized, borrowing features from a diversity of religions and synthesizing them. Even though, in Africa, Islam and traditional religions are not exclusive, there are limits to what Islam can absorb.

Syncretism is not acceptable; or as historian Lamin Sanneh explains, Islam “is syncretist only as a phase or for want of knowing better, not as a permanent state.”7 In the Americas, it could hardly accommodate such elements as the concept of multiple deities, considered heresy. Shirk, the belief that God’s divinity may be shared, is, according to the Qur’an, the most heinous and unforgivable sin. As far as Christianity was concerned, orthodox Islam had already stated quite clearly what was acceptable in it and what was not.

To introduce other crucial beliefs, such as the Trinity or that Jesus was the son of God, would have been sacrilegious. Since syncretism was not an option and the possibilities of transmission of the orthodoxy were limited, only one avenue was left for African Islam in the Americas: it could only disappear with the last Africans, enslaved, recaptives, or indentured laborers.

Abd al-Rahman al-Baghdadi’s experience in Brazil sheds light on the last decades of Islam and its believers. A group of men had come to him in Rio, arguing, “We just want you to teach us the right religion, because we thought that we were the only Muslims in this world, that we were on the right path, and that all the white communities were Christians. Until, Allah almighty bestowed his gifts and we saw you and realized that the possessions of the Creator are large and not uninhabited but full of Muslims.”

They acknowledged that it would be difficult for them to immigrate to Muslim lands because they would have to leave all their property to the state. It was the same reason that had pushed some Trinidadian Muslims to abandon their repatriation effort. Al-Baghdadi ended up teaching a group of five hundred people who had been duped by a man, Ahmad, who presented himself as a Muslim from Tangier, Morocco.

Many Muslims had been deported young and did not have a deep knowledge of the religion, so not knowing better, they had followed his lead. But, according to al-Baghdadi, he “started teaching them the Jewish religion gradually.” He also convinced them that to convert to Islam one needed to pay. Ahmad acknowledged to al-Baghdadi that his goal had been “to harm the Muslims.” This episode shows how much knowledge could be lost by some Muslims, depending on their age at capture; but as significant was their eagerness to go back to orthodoxy.8

In various places, some Muslims read the Bible and were active in the church, but, as noted earlier, they were also using their Arabic literacy to discreetly write religious and secular manuscripts in which they clearly identified themselves as Muslims. Others, in Brazil, were members of black Catholic fraternities. In Bahia, for example, Gibirilu (from the Arabic Jibril, Gabriel), also known as Manoel Nascimento de Santo Silva, belonged to the Sociedade Protectora dos Desvalidos (Society for the Protection of the Destitute). His father was Alufa Salu, an imam born in Ife, Nigeria. His maternal grandfather, also a Muslim, was born in Brazil, the son a Nupe Muslim deported from Nigeria.9 Despite his Catholic affiliation, Gibirilu, who died in 1959, was considered one of the last “orthodox” Muslims in the city.

A similar phenomenon was recorded in the Sea Islands. According to one of Bilali’s descendants, a great-granddaughter of Bilali Mohamed, Harriet Hall, was a Muslim at least until 1866, when the First African Baptist Church came to Sapelo Island.10 Information given by her descendant suggests that she may have remained a Muslim secretly while being active in the church until her death in 1922. Being overtly a Christian had distinct advantages.

In Brazil in particular, belonging to the church black associations distracted the attention of the authorities, which had become actively anti-Muslim after the 1835 rebellion. In the United States, black churches started to blossom and recruit forcefully after Emancipation, and everywhere in the Americas, the church and its associations created and strengthened solidarity in the black population as a whole—an important outcome in a hostile environment. After Emancipation, adherence to Christianity on the part of the Muslims may have been a way of disguising and protecting their true faith while taking advantage of positive and useful structures.

What is striking in all these cases is that the Muslims did not mix Christianity and Islam; their activities in the church and their Islamic faith remained separate. As Pierre Verger perceptively remarked, “This juxtaposition of two religions that were so intransigent and exclusive … had nothing to do with syncretism between two religions.”11 As exemplified in the communities visited by al-Baghdadi, some Islamic beliefs and rites could be denatured, but it was the result of ignorance, not of a conscious, deliberate attempt at syncretism. This willingness to keep the religion “pristine” in the most difficult circumstances participated in its disappearance.

Islamic Survivals in Other Religions

Islam practiced by the children of African Muslims was still Islam, but this situation soon became exceptional, for orthodox Islam died out. Yet it did not wholly disappear; parts of the religion survived as a number of its traits were incorporated into other African religions with which it had existed side by side. For various reasons, such as concentration of followers, ongoing contact with Africa, adaptability, and tolerance of syncretism, a number of African-based or African-derived religions have remained. They have expanded and stopped being the religion of a particular ethnic group to become the religion of peoples of different origins, all of whom brought something to the new creed and liturgy.

No systematic research has been conducted yet on Islam’s contribution to the African-derived religions of the Americas, and how some of its elements found their way into Candomble, Santeria, Vodun, and other rites is not known. But the observation of similar phenomenon in Africa may shed light on what happened in the Americas. In Africa, in the contact zones between Muslims and non- Muslims, where they share the same villages and towns, for example, interaction and….

To read more about the Servants Of Allah By Sylviane A Diouf book Click the download button below to get it for free

or

Report broken link

Support this Website

for websites