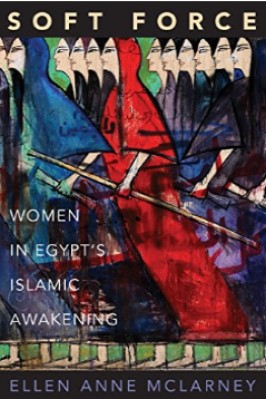

Soft Force: Women in Egypt’s Islamic Awakening

| Soft Force |

| Ellen Anne McLarney |

| 331 |

| |

| PDF Direct Download Link |

| Click for Hard Copy from Amazon |

SOFT FORCE – Book Sample

The Islamic Public Sphere and the Subject of Gender:

The Politics of the Personal

One of the most visible public faces of the 2011 revolution in Egypt was Asmaʾ Mahfouz, a young woman who posted a video blog on Face-book calling for the January 25 protest in Tahrir Square “so that maybe we the country can become free, can become a country with justice, a country with dignity, a country in which a human can be truly human, not living like an animal.”1

She describes a stark imbalance of power: a lone girl standing against the security apparatus of the state. When she initially went out to demonstrate, only three other people came to join her. They were met with vans full of security forces, “tens of thugs” (balṭagiyyīn) that menaced the small band of protesters. Talking about her fear (ruʿb), she epitomizes the voice of righteous indignation against the Goliath of an abusive military regime. “I am a girl,” she says, “and I went down.”

The skinny, small, pale girl bundled up in her winter scarf and sweater speaks clearly and forcefully, despite a slight speech impediment, rallying a political community to action against tyrannical rule. Mahfouz’s vlog is not necessarily famous for actually sparking the revolution, as some have claimed in the revolution’s af-termath. Rather, she visually embodies and vocally advocates what the Islamic activist Heba Raouf Ezzat calls “soft force,” al-quwwaal-nāʿima.

Raouf Ezzat uses the term to refer to nonviolent protest, or what she calls “women’s jihad,” wielded against “tyrannical government.”2 Connoting a kind of feminized smoothness, goodness, and grace, niʿma is wielded as a weapon against what political scientist Paul Amar calls the “thug state.”3 Resonating with connotations of righteousness, it is a keyword used for imagining and creating a just society rooted in the grace of the right path.

“Soft force” is the gradual institutional change— and the war of ideas— that has been one of Islamic organizations’ most powerful tools in Egypt. The concept of soft force found its way into the controversial 2012 constitution, authored by the Islamist government of Muhammad Morsi. The constitution’s eleventh and final principle stated:

Egypt’s pioneering intellectual and cultural leadership embodies her soft force (quwāhāal-nāʿima), exemplified in the gift of free-dom of her intellectuals and creators, her universities, her linguis-tic and scientific organizations, her research centers, her press, her arts, her letters, and her media, her national church, and her noble Azhar that was throughout its history a foundation of the identity of the nation, protecting the eternal Arabic language and the Islamic shariʿa, as a beacon (manāra) of enlightened, moder-ate thought.4

This book is about the soft force of Islamic cultural production in the decades leading up to the 2011 revolution in Egypt. It is about the passive revolution of Islamic popular culture, mass media, and pub-lic scholarship, a war of position developed within the structures of a semiauthoritarian, neoliberal state.5 It is about the role women play in articulating that revolution, in their writings, activism, and discursive transformation of Egypt’s social, cultural, and political institutions.

It is intended as an antidote to dominant representations of women as op-pressed by Islamic politics, movements, and groups. SoftForce details women’s contribution to the emergence of an Islamic public sphere— one that has trenchantly critiqued successive dictatorships in Egypt, partly through a liberal ideology of rights, democracy, freedom, equal-ity, and family values. Women’s Islamic cultural production— their lec tures, pamphlets, theses, books, magazines, newspapers, television Introduction shows, films, and Internet postings— has been a critical instrument of this soft revolution.

The Islamic family, a bastion of Islamic law and a site for the cultiva-tion of Islamic subjectivities, has been a central axis of public discus-sions of an Islamic politics. The private sphere of intimate relations has been the site of a particularly intense process of creative self- fashioning, a place for cultivating the techniques of self so critical to Muslim piety in the age of the Islamic awakening.6

In Islamist intellectual and cul-tural production, women are interpreted as having a privileged role in overseeing the transmission and reproduction of these techniques of self. They do this partly through the biological reproduction of the Islamic umma (the Islamic community) but also through its ideological reproduction.

They not only participate in the inculcation of new Islamic citizen subjects through the labor of childrearing but also dis-cursively construct new gendered subjects through their cultural pro-duction.

The revivalist preacher and writer Niʿmat Sidqi describes this as the different dimensions of jihad, talking about jihad of the tongue, of the pen, of education, and even of childrearing.7 She interprets the classical Islamic concept of jihad in novel ways, reorienting the struggle for an Islamic society in femininized spheres of influence, concepts that would be taken up by later Islamic thinkers like Heba Raouf Ezzat.

A women’s jihad of childrearing assumes an essentialized femininity of biological motherhood, an essence that revivalist writers see as the jawhar (core, interior, gem, jewel) of a resplendent, luminous mate-rial world harmonized to the divine order.

This jawhar, or essence, is also the core of a resplendent, luminous self— one that is enlightened, awakened, and revived by the divine word.8 It is priceless and must be protected and safeguarded but also polished and hewn to shine. Jawhar is a kind of spiritual interior cultivated through proper Islamic practice but also refers, in an almost erotic way, to the female body’s material beauty.

The spiritual jawhar described in some of these writings sug-gests Qurʾanic images of paradise (55:22, 56– 58), the rubies and coral that the Qurʾan likens to the chaste women that inhabit the garden, untouched by any man (55:56– 58).

Revivalist writers understand this feminine essence as a source of an instinct for the divine, constructing images that connect women’s softness to God’s grace (niʿma). They talk about fiṭratAllah, the instinct that God implanted in the human breast, guiding human beings to peace, affection, and mercy (30:21, 30).

In contrast to the stain of Christianity’s original sin, fiṭratAllah suggests an essential goodness in the material world of the female body, a femi-nine grace that smooths the path for the social, biological, and ideo-logical reproduction of the Islamic community, the umma.

Women’s Words: An Islamic Body of Texts

Through the life and work of a series of prolific public intellectuals, SoftForce chronicles women’s role in the awakening of Islamic senti-ments, sensibilities, and senses in Egypt. The authors are professors (Bint al- Shatiʾ) and preachers (Niʿmat Sidqi), journalists (Iman Mus-tafa) and theater critics (Safinaz Kazim), polemicists (Muhammad ʿImara, Muhammad Jalal Kishk) and activists (Heba Raouf Ezzat, Za-ynab al- Ghazali), Azharis (ʿAbd al- Wahid Wafi) and muftis (ʿAtiyya Saqr), actresses (Shams al- Barudi) and television personalities (Kari-man Hamza), wives and mothers.

Their diverse nature— hailing from different disciplines, social milieus, and institutions; writing in differ-ent genres and styles; publishing in different outlets— speaks to the multifarious nature of the revival. Rather than a single movement, the ṣaḥwa (awakening) is a broad set of processes that has contributed to the revival of religious commitments and the circulation of religious materials articulating those commitments.

I draw on a variety of forms: fatwas, sermons, lectures, theses, biographies, political essays, news-paper articles, scholarly essays, and exegeses of the Qurʾan, as well as websites, Facebook postings, Tweets, and YouTube videos. The echoing of a set of similar themes— about family, gendered identities, and women’s rights and responsibilities in an Islamic society— suggests the consolidation of a hegemonic position around these issues in Islamic thought.

Echoes of similar understandings of women’s rights, roles, du-ties, and relationship to the family can be found across the umma.9

It is through this shared world of Islamic letters that the revival has been able to imagine itself as an integral whole, cultivating gendered subjectivities understood to underpin both an Islamic cosmology and an Islamic praxis. Moreover, it is a vision of Islamic womanhood that has proliferated throughout the Islamic umma, as ideas about women’s roles and women’s work, women’s knowledge, and women’s bodies

To read more about the Soft Force book Click the download button below to get it for free

Report broken link

Support this Website

for websites