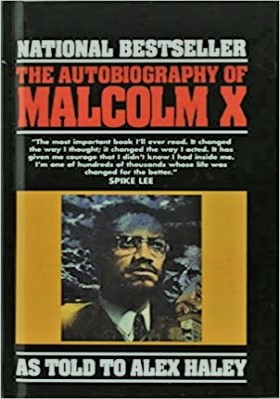

| The Autobiography Of Malcolm X |

| Malcolm X |

| 518 |

| 3 Mb |

| |

| PDF Direct Download Link |

| Click for Hard Copy from Amazon |

The Autobiography of Malcolm X – Book Sample

NIGHTMARE – The Autobiography of Malcolm X

When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home in Omaha, Nebraska, one night.

Surrounding the house, brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out. My mother went to the front door and opened it.

Standing where they could see her pregnant condition, she told them that she was alone with her three small children, and that my father was away, preaching, in Milwaukee. The Klansmen shouted threats and warnings at her that we had better get out of town because “the good Christian white people” were not going to stand for my father’s “spreading trouble” among the “good” Negroes of Omaha with the “back to Africa” preachings of Marcus Garvey.

My father, the Reverend Earl Little, was a Baptist minister, a dedicated organizer for Marcus Aurelius Garvey’s U.N.I.A. (Universal Negro Improvement Association).

With the help of such disciples as my father, Garvey, from his headquarters in New York City’s Harlem, was raising the banner of black-race purity and exhorting the Negro masses to return to their ancestral African homeland—a cause which had made Garvey the most controversial black man on earth.

Still shouting threats, the Klansmen finally spurred their horses and galloped around the house, shattering every window pane with their gun butts.

Then they rode off into the night, their torches flaring, as suddenly as they had come. My father was enraged when he returned. He decided to wait until I was born—which would be soon—and then the family would move. I am not sure why he made this decision, for he was not a frightened Negro, as most then were, and many still are today.

My father was a big, six-foot-four, very black man. He had only one eye. How he had lost the other one I have never known. He was from Reynolds, Georgia, where he had left school after the third or maybe fourth grade.

He believed, as did Marcus Garvey, that freedom, independence and self-respect could never be achieved by the Negro in America, and that therefore the Negro should leave America to the white man and return to his African land of origin.

Among the reasons my father had decided to risk and dedicate his life to help disseminate this philosophy among his people was that he had seen four of his six brothers die by violence, three of them killed by white men, including one by lynching.

What my father could not know then was that of the remaining three, including himself, only one, my Uncle Jim, would die in bed, of natural causes.

Northern white police were later to shoot my Uncle Oscar. And my father was finally himself to die by the white man’s hands. It has always been my belief that I, too, will die by violence. I have done all that I can to be prepared.

I was my father’s seventh child. He had three children by a previous marriage—Ella, Earl, and Mary, who lived in Boston. He had met and married my mother in Philadelphia, where their first child, my oldest full brother, Wilfred, was born.

They moved from Philadelphia to Omaha, where Hilda and then Philbert were born. I was next in line. My mother was twenty-eight when I was born on May 19, 1925, in an Omaha hospital. Then we moved to Milwaukee, where Reginald was born. From infancy, he had some kind of hernia condition which was to handicap him physically for the rest of his life. Lo…

MASCOT – The Autobiography of Malcolm X

On June twenty-seventh of that year, nineteen thirty-seven, Joe Louis knocked out James J. Braddock to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

And all the Negroes in Lansing, like Negroes everywhere, went wildly happy with the greatest celebration of race pride our generation had ever known. Every Negro boy old enough to walk wanted to be the next Brown Bomber. My brother Philbert, who had already become a pretty good boxer in school, was no exception. (I was trying to play basketball.

I was gangling and tall, but I wasn’t very good at it—too awkward.) In the fall of that year, Philbert entered the amateur bouts that were held in Lansing’s Prudden Auditorium. He did well, surviving the increasingly tough eliminations.

I would go down to the gym and watch him train. It was very exciting. Perhaps without realizing it I became secretly envious; for one thing, I know I could not help seeing some of my younger broth Reginald’s lifelong admiration for me getting siphoned off to Philbert. People praised Philbert as a natural boxer.

I figured that since we belonged to the same family, maybe I would become one, too. So I put myself in the ring. I think I was thirteen when I signed up for my first bout, but my height and raw-boned frame let me get away with claiming that I was sixteen, the minimum age—and my weight of about 128 pounds got me classified as a bantamweight.

They matched me with a white boy, a novice like myself, named Bill Peterson. I’ll never forget him. When our turn in the next amateur bouts came up, all of my brothers and sisters were there watching, along with just about everyone else I knew in town. They were there not so much because of me but because of Philbert, who…

“HOMEBOY”

I looked like Li’l Abner. Mason, Michigan, was written all over me. My kinky, reddish hair was cut hick style, and I didn’t even use grease in it. My green suit’s coat sleeves stopped above my wrists, the pants legs showed three inches of socks. Just a shade lighter green than the suit was my narrow-collared, three-quarter length Lansing department store topcoat.

My appearance was too much for even Ella. But she told me later she had seen countrified members of the Little family come up from Georgia in even worse shape than I was. Ella had fixed up a nice little upstairs room for me. And she was truly a Georgia Negro woman when she got into the kitchen with her pots and pans.

She was the kind of cook who would heap up your plate with such as ham hock, greens, black-eyed peas, fried fish, cabbage, sweet potatoes, grits and gravy, and cornbread. And the more you put away the better she felt. I worked out at Ella’s kitchen table like there was no tomorrow.

Ella still seemed to be as big, black, outspoken and impressive a woman as she had been in Mason and Lansing. Only about two weeks before I arrived, she had split up with her second husband— the soldier, Frank, whom I had met there the previous summer; but she was taking it right in stride.

I could see, though I didn’t say, how any average man would find it almost impossible to live for very long with a woman whose every instinct was to run everything and everybody she had anything to do with—including me.

About my second day there in Roxbury, Ella told me that she didn’t want me to start hunting for a job right away, like most newcomer Negroes did. She said that she had told all those she’d brought North to take their time, to walk around, to travel the buses and the subway, and get the

LAURA – The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Shorty would take me to groovy, frantic scenes in different chicks’ and cats’ pads, where with the lights and juke down mellow, everybody blew gage and juiced back and jumped. I met chicks who were fine as May wine, and cats who were hip to all happenings.

That paragraph is deliberate, of course; it’s just to display a bit more of the slang that was used by everyone I respected as “hip” in those days. And in no time at all, I was talking the slang like a lifelong hipster.

Like hundreds of thousands of country-bred Negroes who had come to the Northern black ghetto before me, and have come since, I’d also acquired all the other fashionable ghetto adornments—the zoot suits and conk that I have described, liquor, cigarettes, then reefers—all to erase my embarrassing background. But I still harbored one secret humiliation: I couldn’t dance.

I can’t remember when it was that I actually learned how—that is to say, I can’t recall the specific night or nights. But dancing was the chief action at those “pad parties,” so I’ve no doubt about how and why my initiation into lindy-hopping came about.

With alcohol or marijuana lightening my head, and that wild music wailing away on those portable record players, it didn’t take long to loosen up the dancing instincts in my African heritage.

All I remember is that during some party around this time, when nearly everyone but me was up dancing, some girl grabbed me—they often would take the initiative and grab a partner, for no girl at those parties ever would dream that anyone present couldn’t dance—and there I was out on the floor.

To read more about the The Autobiography Of Malcolm X book Click the download button below to get it for free

or

or

Don't Miss out any Book Click Join OpenMaktaba Telegram group

Don't Miss out any Book Click Join OpenMaktaba Telegram group