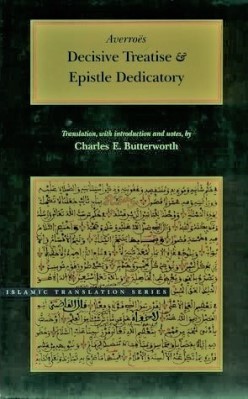

THE BOOK OF THE DECISIVE TREATISE, DETERMINING THE CONNECTION BETWEEN THE LAW AND WISDOM

| The Book Of The Decisive Treatise |

| ibn rushd (Averroes) |

| 33 |

| 0.1 Mb |

| |

| PDF Direct Download Link |

| Click for Hard Copy from Amazon |

The book of the decisive treatise – Sample Book

THE BOOK OF THE DECISIVE TREATISE, DETERMINING THE CONNECTION BETWEEN THE LAW AND WISDOM

In the name of God, the Merciful and the Compassionate; may God be prayed to for Muhammad and his family and may they be accorded peace.

INTRODUCTION – The book of the decisive treatise

- The jurist, imam, judge, and uniquely learned Abū

al-Walīd Muh.ammad Ibn Ah.mad Ibn Rushd, may God be pleased with him, said: Praise be to God with all praises and a prayer for

Muhammad, His chosen servant and messenger. Now the goal of this statement is for us to investigate, from the perspective of Law- based ((Unless otherwise indicated, the term translated throughout this treatise as “Law” is sharī ‘a or its equivalent, shar ‘. In this treatise, the terms are used to refer only to the revealed law of Islam. Elsewhere, however, Averroes uses the term sharī ‘a to refer to revealed law generally. Because the term “legal” may be misleading for modern readers, even when capitalized and rendered “Legal,” the adjectival form of sharī ‘a — that is, shar ‘ī — is rendered here as “Law-based.”

In his justly famous manual of law, Averroes explains that the jurists acknowledge the judgments of the divine Law to fall into five categories: obligatory (wājib), recommended (mandūb),

prohibited (mah.z.ūr), reprehensible (makrūh), and permitted

(mubāh.). Here, however, he groups the first two under a more comprehensive category of “commanded” (mamūr) and — perhaps

since it is not applicable to the present question — passes over “reprehensible” in silence; see Bidāyat al-Mujtahid wa Nihāyat

al-Muqtas.id, ed. ‘Abd al-H.alīm Muh.ammad ‘Abd al-H.alīm and ‘Abd al-Rah.mān H.asan Mah.mūd (Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-H.adītha, 1975), vol. 1, pp. 17-18. The alliterative title, pointing to the

work’s character as a primer of Islamic law, can be rendered in English as The Legal Interpreter’s Beginning and The Mediator’s Ending.)) reflection, whether reflection upon philosophy and the sciences of logic is permitted, prohibited, or commanded — and this as a recommendation or as an obligation — by the Law.

[II. THAT PHILOSOPHY AND LOGIC ARE OBLIGATORY] [A. THAT PHILOSOPHY IS OBLIGATORY]

- So we say: If the activity of philosophy is nothing more than reflection upon existing things and consideration of them insofar as they are an indication of the Artisan — I mean, insofar as they are artifacts, for existing things indicate the Artisan only through cognizance ((The term is ma ‘rifa. Similarly, ‘arafa is translated as “to be cognizant” and ‘ārif as “cognizant” or “one who is cognizant.” ‘Ilm, on the other hand, is translated as “knowledge” or

“science,” ‘alima as “to know,” and ‘ālim as “knower” or

“learned.” It is important to preserve the distinctions between the Arabic terms in English — distinctions that seem to reflect those between gignōskein and epistasthai in Greek — because Averroes goes on to speak of human cognizance of God as well as of God’s knowledge of particulars (see below sects. 4 and 17))) of the art in them, and the more complete cognizance of the art in them is, the more complete is cognizance of the Artisan — and if the Law has recommended and urged consideration of existing things, then it is evident that what this name indicates is either obligatory or recommended by the Law.

That the Law calls for consideration of existing things by means of the intellect and for pursuing cognizance of them by means of it is evident from various verses in the Book of God, may He be blessed and exalted ((In this treatise, Averroes uses the terms “book of God” and “precious book” to indicate the Quran. The numbers within parentheses refer to chapters and verses of the Quran. All translations from the Quran are my own)). There is His statement, may He be exalted, “Consider, you who have sight” (59:2); this is a text for the obligation of using both intellectual and Law-based syllogistic reasoning ((Normally the term qiyās is translated as “syllogism,” this being an abridgment of “syllogistic reasoning.”

Here, and in what follows, I translate it as “syllogistic reasoning” in order to bring out the way Averroes seems to be using the term)). And there is His statement, may He be exalted, “Have they not reflected upon the kingdoms of the heavens and the earth and what things God has created?” (7:185); this is a text urging reflection upon all existing things. And God, may He be exalted, has made it known that one of those whom He selected and venerated by means of this knowledge was Abraham, peace upon him; thus He, may He be exalted, said: “And in this way we made Abraham see the kingdoms of the heavens and the

earth, that he might be . . .” [and so on to the end of] the verse ((6:75)) ((The rest of the verse reads: “. . . one of those who have certainty.”)). And He, may He be exalted, said: “Do they not reflect upon the camels, how they have been created, and upon the heaven, how it has been raised up?” ((88:17)). And He said: “And they ponder the creation of the heavens and the earth” ((3:191)), and so on in innumerable other verses.

B. THE CASE FOR SYLLOGISTIC REASONING – The book of the decisive treatise

- Since it has been determined that the Law makes it obligatory to reflect upon existing things by means of the intellect and to consider them; and consideration is nothing more than inferring and drawing out the unknown from the known; and this is syllogistic reasoning or by means of syllogistic reasoning; therefore, it is obligatory that we go about reflecting upon the existing things by means of intellectual syllogistic reasoning. And it is evident that this manner of reflection the Law calls for and urges is the most complete kind of reflection by means of the most complete kind of syllogistic reasoning and is the one called “demonstration.”

- Since the Law has urged cognizance of God, may He be exalted, and of all of the things existing through Him by means of demonstration; and it is preferable or even necessary that anyone who wants to know God, may He be blessed and exalted, and all of the existing things by means of demonstration set out first to know the kinds of demonstrations, their conditions, and in what [way] demonstrative syllogistic reasoning differs from dialectical, rhetorical, and sophistical syllogistic reasoning; and that is not possible unless, prior to that, he sets out to become cognizant of what unqualified syllogistic reasoning is, how many kinds of it there are, and which of them is syllogistic reasoning and which not; and that is not possible either unless, prior to that, he sets out to become cognizant of the parts of which syllogistic reasoning is composed — I mean, the premises and their kinds; therefore, the one who has faith ((The term is al-mumin. Throughout this treatise amana is translated as “to have faith” and īmān as “faith”; while i ‘taqada is translated as “to believe,” mu ‘taqid as “believer,” and

- i ‘tiqād as “belief.”)) in the Law and follows its command to reflect upon existing things perhaps comes under the obligation to set out, before reflecting, to become cognizant of these things whose status [3] with respect to reflection is that of tools to work.

For just as the jurist infers from the command to obtain juridical understanding of the statutes the obligation to become cognizant of the kinds of juridical syllogistic reasoning and which of them is syllogistic reasoning and which not, so, too, is it obligatory for the one cognizant [of God] to infer from the command to reflect upon the beings the obligation to become cognizant of intellectual syllogistic reasoning and its kinds. Nay, it is even more fitting that he do so, for if the jurist infers from His statement, may He be exalted, “Consider, you who have sight” (59:2), the obligation to become cognizant of juridical syllogistic reasoning, then how much more fitting is it that the one cognizant of God infer from that the obligation to become cognizant of intellectual syllogistic reasoning.

Intellectual syllogistic reasoning

It is not for someone to say: “Now this kind of reflection about intellectual syllogistic reasoning is a heretical innovation since it did not exist in the earliest days [of Islam].” For reflection upon juridical syllogistic reasoning and its kinds is also something inferred after the earliest days; yet it is not opined to be a heretical innovation. So it is obligatory to believe the same about reflection upon intellectual syllogistic reasoning — and for this there is a reason, but this is not the place to mention it. Moreover, most of the adherents to this religion support intellectual syllogistic reasoning except for a small group of strict literalists, and they are refuted by the texts [of the Quran].

- Since it has been determined that the Law makes reflection upon intellectual syllogistic reasoning and its kinds obligatory, just as it makes reflection upon juridical syllogistic reasoning obligatory; therefore, it is evident that, if someone prior to us has not set out to investigate intellectual syllogistic reasoning and its kinds, it is obligatory for us to begin to investigate it and for the one who comes after to rely upon the one who preceded ((The term is al-mutaqaddim and comes from the same verb tht has been translated heretofore as “set out,” namely, taqaddama.)) so that cognizance of it might be perfected. For it is difficult or impossible for one person to grasp all that he needs of this by himself and from the beginning, just as it is difficult for one person to infer all he needs to be cognizant of concerning the kinds of juridical syllogistic reasoning. Nay, this is even more the case with being cognizant of intellectual syllogistic reasoning.

- If someone other than us has already investigated that, it is evidently obligatory for us to rely on what the one who has preceded us says about what we are pursuing, regardless of whether that other person shares our religion or not. For when a valid sacrifice is performed by means of a tool, [4] no consideration is given, with respect to the validity of the sacrifice, as to whether the tool belongs to someone who shares in our religion or not so long as it fulfills the conditions for validity. And by “not sharing [in our religion],” I mean those Ancients who reflected upon these things before the religion of Islam.

- Since this is the case; and all that is needed with respect to reflection about the matter of intellectual syllogistic reasonings has been investigated by the Ancients in the most complete manner; therefore, we ought perhaps to seize their books in our hands and reflect upon what they have said about that. And if it is all correct, we will accept it from them; whereas if there is anything not correct in it, we will alert [people] to it.

The book of the decisive treatise

- Since we have finished with this type of reflection and have acquired the tools by which we are able to consider existing things and the indication of artfulness in them — for one who is not cognizant of the artfulness is not cognizant of what has been artfully made, and one who is not cognizant of what has been artfully made is not cognizant of the Artisan — therefore, it is perhaps obligatory that we start investigating existing things according to the order and manner we have gained from the art of becoming cognizant about demonstrative syllogisms. It is evident, moreover, that this goal is completed for us with respect to existing things only when they are investigated successively by one person after another and when in doing so the one coming after makes use of the one having preceded — along the lines of what occurs in the mathematical sciences.

For, if we were to assume the art of geometry and likewise the art of astronomy to be non-existent in this time of ours, and if a single man wished to discern on his own the sizes of the heavenly bodies, their shapes, and their distances from one another, that would not be possible for him — for example, to become cognizant of the size of the sun with respect to the earth and other things about the sizes of the planets — not even if he were by nature the most intelligent person, unless it were by means of revelation or something resembling revelation.

The book of the decisive treatise

Indeed, if it were said to him that the sun is about 150 or 160 times greater than the earth, he would count this statement as madness on the part of the one who makes it ((Actually, if the diameter of the earth is used as the unit of measure, it is about 109 times greater.)). And this is something for which a demonstration has been brought forth in astronomy and which no one adept in that science doubts.

There is hardly any need to use an example from the art of mathematics, for reflection upon this art [5] of the roots of jurisprudence, and jurisprudence itself, has been perfected only over a long period of time.

If someone today wished to grasp on his own all of the proofs inferred by those in the legal schools who reflect upon the controversial questions debated ((The term is munāz.ara and has the same root as Nazar, translated throughout this treatise as “reflection.”)) in most Islamic countries, even excepting the Maghrib ((That is, the Western part of the Islamic world —

North Africa and Spain)), he would deserve to be laughed at because that would be impossible for him — in addition to having already been done. This is a self-evident matter not only with respect to the scientific arts but also with respect to the practical ones.

For there is not an art among them that a single person can bring about on his own. So how can this be done with the art of arts, namely, wisdom? ((As is evident from the sub-title of the treatise, h.ikma (“wisdom”) is used interchangeably with falsafa to mean philosophy. Nonetheless, the original difference between the two is respected here in that h.ikma is always translated as “wisdom” and falsafa as “philosophy.”))

To read more about the The Book Of The Decisive Treatise book Click the download button below to get it for free

or

or

for websites

Don't Miss out any Book Click Join OpenMaktaba Telegram group

Don't Miss out any Book Click Join OpenMaktaba Telegram group